Contributions and Interviews

The transition from LIBOR – TP Perspective

21. 12. 2021

The Interbank Offered Rates (“IBORs”), including the London Interbank Offered Rate (“LIBOR”), the Euro Interbank Offered Rate (“EURIBOR”) and the Euro Overnight Index Average (“EONIA”), are well known and used to be widely accepted benchmark interest rates by tax professionals all around the world. They served as a widely accepted benchmark for short-term interest rates and provided an indication of the average rate at which a panel of banks could obtain wholesale, unsecured funding for set periods in several currencies such as GBP, USD, EUR, CHF and JPY. LIBOR and the other IBORs are used globally to price many types of financial products, including loans, bonds, derivatives and mortgages.

However, the chapter of IBORs will soon be closed, as the use of some of these interest rates will cease, and others will be reformed. Most of them will be replaced by “Risk-Free Rates”, also known as “Near Risk-Free Rates” (“RFRs”) and other alternative rates. RFRs are primarily based on active and liquid underlying markets, and therefore are considered more robust and reliable. In other words, RFRs will typically be based on a weighted average of actual transactions instead of an estimate provided by each of the panel banks.

How did we get to that point?

In 2012, a storm of opprobrium broke around the alleged manipulation of LIBOR by various panel banks, resulting in regulatory penalties amounting to several billion dollars and driving a series of reforms in the process to determine LIBOR.

In 2014, the Financial Stability Board (“FSB”) recommended a reform of IBORs and their replacement by RFRs that are based on more active and liquid overnight lending markets.

Some financial authorities have stated that IBORs, which should reflect the interbank lending market trends, are no longer accurate or liquid. In respect of LIBOR, Andrew Bailey (Governor of the Bank of England) stated in July 2020: “The low levels of underlying activity make it fragile and more susceptible to liquidity and amplification effects in financial markets”.[1]

On 5 March 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) (UK regulator) confirmed that all LIBOR settings for all currencies would either cease to be provided by any administrator or no longer be representative from the following dates:

- 31 December 2021, for Sterling, Euro, Swiss Franc and Japanese Yen, and US Dollar 1-week and 2-month settings; and

- 30 June 2023, for the remaining US Dollar settings, i.e., 1-month, 3-month, 6-month and 12-month.[1]

Accordingly, the European Union (“EU”) also took steps in the same direction. The EU also adopted the new Benchmark Regulation 2016/2011 (“BMR”) to regulate benchmarks used in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds. According to the new BMR, only compliant benchmarks provided by registered or authorized administrators may be used in new contracts after 1 January 2020.

The EU institutions later agreed to grant providers of critical benchmarks – including LIBOR and EURIBOR – 2 extra years until 31 December 2021 to comply with the new BMR.

What are the new benchmarks?

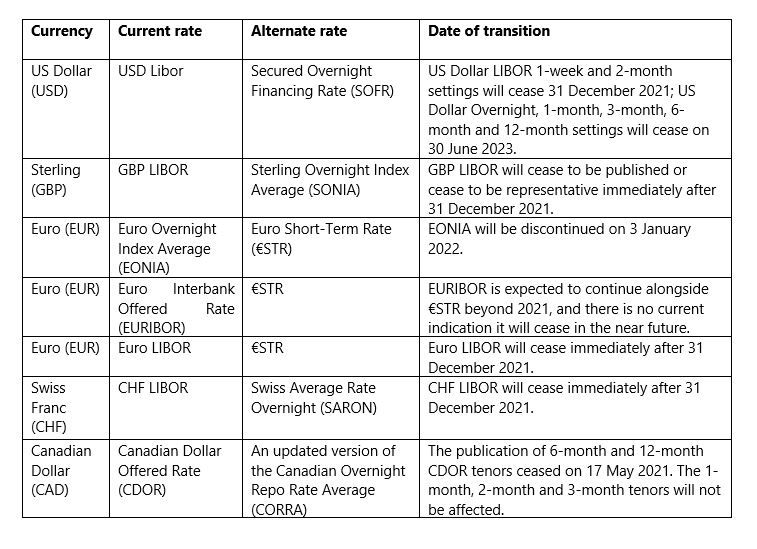

The new rates[3] that tax specialists may rely upon are as the following:

What would be the tax and transfer pricing consequences stemming from the transition?

Besides the new benchmarks used in various TP studies, tax specialists and businesses should consider the existing arrangements and act accordingly.

- Financial services

All existing financial agreements should be considered and modified to the new benchmarks. Financial products that are sold to clients and/or hedging instruments and financing arrangements that explicitly refer to the IBORs would need significant modification. Additionally, new financial arrangements would have to comply with the new RFSs, and all legal and tax departments should adapt their existing contracts accordingly.

- Intercompany agreements

Some intercompany agreements might have fallback clauses for cases of discontinuation of LIBOR. Nonetheless, companies should make appropriate modifications to the existing agreements.

- Cash-pooling agreements

Special attention should be given to the cash-pooling agreements set up in multinational companies. In-house banks that perform hedging for the group will be impacted by LIBOR discontinuation, given the common use of LIBOR as a reference rate in hedging contracts. Therefore, the agreements should be modified under the new reference rates, and the tax specialist should assess what impact the change would have on the intra-group financing.

- Arm’s length principle

The assessment of the arm’s length principle in financial transactions would need specific attention. According to the OECD TP Guidance on Financial Transactions from February 2020, the arm’s length nature of loans, in particular, is determined taking into consideration the amount of the loan, its maturity, the schedule of repayment, the nature or purpose of the loan (trade credit, merger/acquisition, mortgage, etc.), level of seniority and subordination, geographical location of the borrower, currency, collateral provided, presence and quality of any guarantee, and whether the interest rate is fixed or floating. Undoubtedly, when LIBOR rates are replaced with an RFR in a contract, the underlying risk, the payment flows, etc., will change. This needs to be considered in the comparability analysis, and often comparability adjustments will need to be made if the uncontrolled transactions are LIBOR-based and the tested transaction is RFR-based.

Conclusion

The end of LIBOR is certainly a new era in TP benchmarking. There would be important tax consequences for many multinational groups regarding their intercompany agreements and transfer pricing documentation. Therefore, implementing the new risk-free interest rates should be planned on time and keeping in mind the characteristics of the new interest rates.

(2) https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/announcements-end-libor